| Item Code: | NAQ463 |

| Author: | Rakhshanda Jalil |

| Publisher: | Harper Collins Publishers |

| Language: | English |

| Edition: | 2018 |

| ISBN: | 9789353020309 |

| Pages: | 240 |

| Cover: | HARDCOVER |

| Other Details | 9.00 X 6.00 inch |

| Weight | 300 gm |

Shahryar: A Life in Poetry is as much a study of a poet's life - the father, friend, teacher and raconteur par excellence - as it is an attempt to write the literary history of contemporary Urdu poetry. Tracing Shahryar's journey as a poet, Rakhshanda Jalil demonstrates how he evolved a set of symbols, images and metaphors that, while seemingly personal, transcended the self and the individual. She also evaluates his work in the light of the two major literary movements that shaped his poetic sensibility - the Progressive Writers' Movement and modernism - while him consistently refused to belong to any one group.

Including a selection of some of Shahryar's best poems - ghazals, nazms and film lyrics - brilliantly translated by the author, the book introduces his poetry to a new generation while evaluating Shahryar's considerable body of work in the trajectory of contemporary Indian writings and his extraordinary contribution to not merely modern Urdu poetry, but, more significantirmodern Indian poetry.

(You have sold the ink of the night To the morning You will be punished some day For the devastation you have wrought)

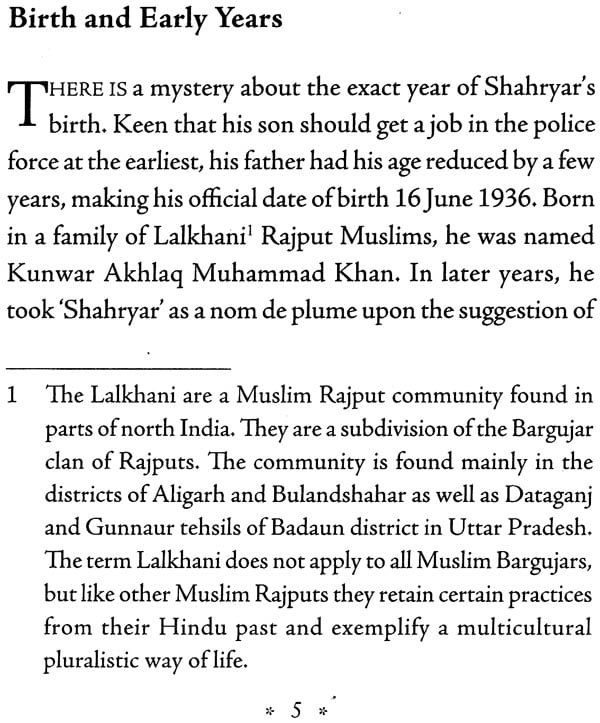

SINCE SHAHRYAR'S death on 13 February 2012, obituaries and tributes have tumbled out - in print, on electronic media and by way of seminars and academic discussions - which harp, in one way or the other, on details of his personal life that have virtually nothing to do with his poetry. A lot of people wish to link the angst and despair, the melancholy and dislocation that we see in some of his poetry, with events and experiences and a sense of loneliness in the poet's own persona and personal life. This seems especially unfortunate since Shahryar was not a particularly lonely man; in fact, he was surrounded by friends and well-wishers and kept in constant touch with his many admirers through his cellphone, which was constantly by his side. Secondly, in seeking this artificial linkage, we are being unfair to Shahryar the poet. A study of his oeuvre in its entirety shows how he evolved a set of symbols, images and metaphors that, while seemingly personal, were crafted precisely so they could transcend the personal and the individual. This evolution mirrors, to some extent, his ambiguous relationship with the two major literary movements that shaped his poetic sensibility - tarraqui pasand tehreek (the Progressive Writers' Movement [PWM]) and jadeediyat (modernism). Also, excessive dwelling on the circumstances of a creative writer's personal life detracts from a critical understanding of his or her work.

In this book I will dwell on his life only insofar as it shapes and affects his work. My concern here is to write a critical biography, one that places Shahryar's poetry in the continuum of modern Urdu poetry. Therefore, this book is as much a study of a poet's life and work as it is an attempt to write the literary history of contemporary Urdu poetry.

Was Shahryar tarraqui pasand or jadeed parast? His critics - and there are many - have maintained that he consistently refused to belong to any one group because he wished to displease neither. I feel this ambiguity is not a sign of weakness but a symbol of his free-spiritedness and refusal to conform. The individualism and romanticism of his early years, as evident in his first collection of poetry, Ism-e Azam (`The Highest Name') published in 1965, soon gave way to an acutely felt concern for the world around him in subsequent collections such as Saatwan Dar ("The Seventh Doorway', 1969) and Hijr ke Mausam (Seasons of Separation', 1978); in fact, as we will see in this study, even in the early days there are poems that defy easy categorization and the sharp distinction between the demands of the two major schools of thought that dominated Urdu poetry from the time Shahryar began his literary career. While refusing to fully adopt the vocabulary of the inquilabi shair (revolutionary poet) favored by the progressives, he refused to write merely to satisfy his own creative self or ease the burden of his soul, thus differing sharply from the jadeed parast as well. Shahryar continued to explore meaningful ways of communication and, in the process, gifted Urdu literature with a unique lexicography, a whole new set of images and symbols. His poetry mirrors the evolution of symbols that, while seeming personal, transcend the self and the individual and speak of universal concerns. I think it is this that lifts his poetry leagues above his contemporaries and it is this singular ability to speak for him while also speaking for the world that defines his entire poetic oeuvre.

Unlike the modernists, Shahryar never bemoaned the futility of communication, nor did he resort to the use of dense, impenetrable images and idioms. I would like to believe that in the age-old debate on Art for Art's Sake v. Art for Life's Sake, Shahryar aligned himself with the latter, despite his avowed refusal to wear a label or a tag.

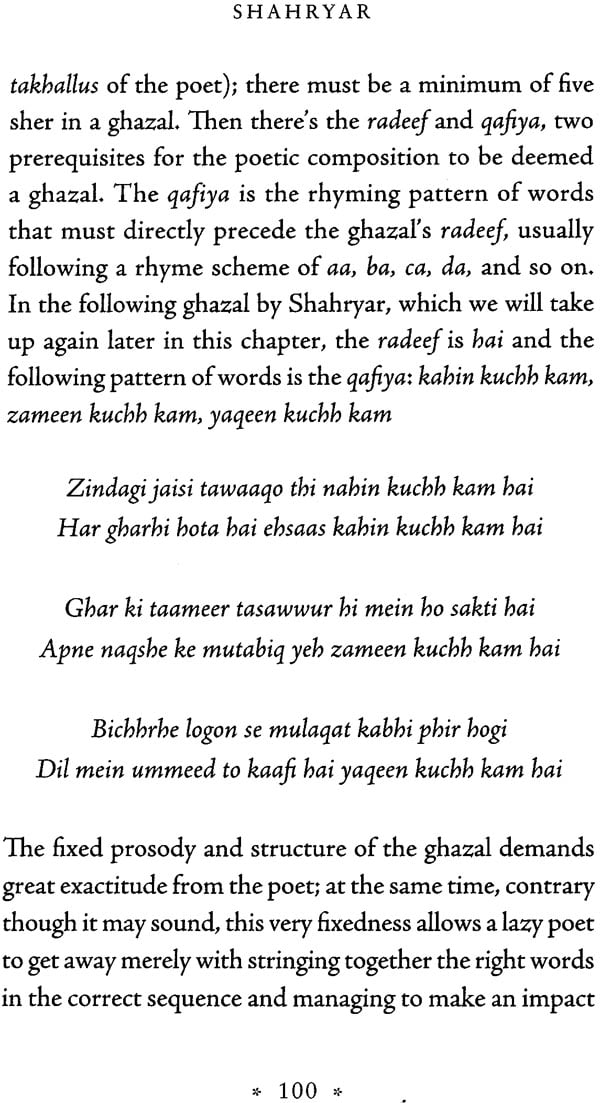

In Shahryar's poetry the image is important. He cloaks it in a magnificent robe of words, words that have a mesmeric spell of their own. As a reader, and especially a critical reader, you have to wrench yourself away from their insistent, inward pull to look again at the image; once out of that tilismic enchantment, you look at the beauty of the image conjured up by the play upon words. It shines through the many layers of meaning in all its crystal clarity, its freshness and poignancy. My experience, both as a reader and translator of Shahryar's poetry, tells me that that is when, maybe, you have reached the core of Shahryar's poetry, felt its newness and its allure in a way that is almost tactile. That is also the point when, perhaps, you have felt yourself drawn through an invisible doorway into the portal of wakefulness.

This book attempts to lay the bare facts of Shahryar's life before the reader; as I have said before, much prurient interest has been displayed in his personal life. While I have tried to flesh out Shahryar the father, friend, teacher and raconteur par excellence, my interest lies primarily in analysing his work, locating it in the trajectory of contemporary Indian writings and evaluating his extraordinary contribution not merely to modern Urdu poetry but, more significantly, modern Indian poetry. It seems especially unfortunate that we - readers and critics alike - seem to categorize writers according to the language in which they write and to box them in a benign parochialism. Shahryar, then, is seen by many as an Urdu poet and not the poet of an age. In the thoughtless ease with which we label poets and writers, we sometimes do them a disservice. My contention in this book is that while indeed Shahryar wrote in Urdu, his poetry is by no means confined to or of interest only to Urdu readers. In writing in the English language about a poet who wrote in Urdu, I am hoping to pull down at least some of the picket fences we construct around our own literatures.

Book's Contents and Sample Pages

Send as free online greeting card