Sarvanga Alpana |

Folk art is the creative

expression of those who uninfluenced by princely ostentation and

ecclesiastic conservatism, revealed in lines and forms what they had

within and around. Her ten-twelve thousand years old creative culture

and a wide-spread art geography apart, India has hundreds of ethnic

groups, each with its own taste, aspirations, joys, sorrows, struggles

and a creative talent. Not in 'word', they discovered in 'form' their

diction, their ultimate means to discourse mutually and with the

'divine'. Education or training wasn't their tool. They had instead

massive imagination, passion to embellish, and inborn ability to give

to routine forms symbolic dimensions, and to things, scattered around,

status of art imagery - all that transformed into artists, not just

individuals but communities, generations after generations. In a world

every minute seeking means to distort and destroy they have kept along

their own tenor singing to their own tunes, dancing to the notes of

their hearts, and discovering in jumble of things, rough crude lines,

and raw colors, a world that breathed purity, harmony, respect and

concern for life, and a strange stoicism.

Defining Folk Arts

It is far easy to identify a

folk form but as much difficult to define. Its definitions vary from

the art of tribes, primitive people, ethnic groups to an art by family

tradition. Race language, a phrase that Gurushaday Datta, a bureaucrat

of colonial India and author of a number of books, used for folk arts,

underlines folk arts' power to communicate. By race he obviously meant

India's indigenous masses other than her west-influenced metropolitan

or urban minority of his days, that is, 1920s-30s. Now this minority of

those days comprises the mainstream of Indian populace, and the

majority of those days is now-days' minority. Thus, what was to Mr.

Datta the language of indigenous majority is now the language of

primitive few.

People's Art As Against Ecclesiastic And Court Art

As against the art of class -

imperial or ecclesiastic, Gurushaday Datta's phrase identifies folk art

as the art of indigenous common masses, whose first specimen was the

nomad. Nomad's rock-shelter art preceded the earliest examples of

priestly or princely art by nine-eight thousand years. Even the painted

Indus wares or terracotta figurines, the transforms of the nomad's art,

preceded the art of court and temples by many centuries, though

subsequently the latter completely isolated the former. Around

11th-12th centuries the illustrative Jain painting revived some of its

elements - irrational anatomy, angularity, bold lines, over

gesticulation. Then onward, elements of this common man's art continued

to have, except in the imperial Mughal painting, a perceptible presence

in Indian painting, even the Sultanate, and the contemporary.

Chhatha Parva - A Typical Folk Festival of Mithila |

Folk art discovers its themes from things around. Every ethnic group

has its own stimuli - things and occasions that emotionally move, which

give each a different character. However, folk art in its entirety

celebrates joy, festivities, ceremonial occasions, and shuns

sensuousness, voluptuous modeling, more vehemently nudeness and all

forms of obscenity. Diction of flesh isn't its idiom. The folk artist

creates forms from within the rituals, myths and legends, by which he

adorns, or rather sanctifies, daily living - things that matter in life.

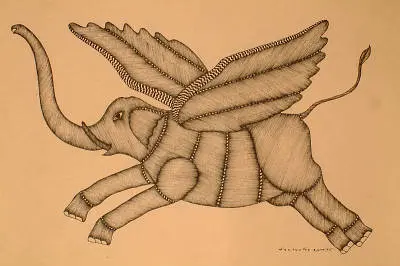

Flying Elephant |

Reason, the tool of science and

classical arts, or even speculative imagination that breeds metaphysics

is not its tool. Here spontaneity substitutes reason. It uses instead

the creative faculty of mind - art imagination, which Coleridge, the

known 18th century Romantic poet of England , calls 'esem-plastic

imagination' - faculty that assimilates and creates. This power to

assimilate gives to folk art its unique mythology - a world beyond

average man's perception, in which the sun and moon have a simultaneous

presence, trees grow over a donkey's head, a tree with a human trunk,

or birds, its foliage.

Mediums And Mind's Width

To be creative is folk mind's

innate nature, to which medium, technique, training... are irrelevant.

In whatever around, a piece of paper, cloth, wood, clay, metal, thrown

away pieces of a waste, it discovers its medium. Wall is very often its

canvas, and for rendering a painting on it a few pieces of thrown away

ropes might suffice. The Sarguja artist will mould them into desired

forms, a bed of flowering plants - stems, branches, twigs, leaves,

flowers, fix them on the wall and paint them with colored muds - white,

ochre, yellow. Ignorant of it, he creates not three-dimensional effects

but a painting with three dimensions. In pieces of rejected iron a

Bastar tribesman finds his material for a statue. Such multiplicity of

material and ability to transform it into an art medium gives to folk

art such generic width, which a single essay might not encompass.

Hence, this study confines to a few of its modes.

Art Of Chhattisgarh: Bastar

Merciless Putanaa |

Every region in Chhattisgarh, a

province in Central India, has a distinct art-form, Sarguja having a

special painting style; Raigarh, metal-casts; Kanker, wood-art;

Kondagaon, terracottas; though it is due to Bastar that Chhattisgarh

has in the world's folk-art map a place which no other art school of

Indian folks can equal. Bastar, a region with over 70 percent tribal

population, has unique talent for almost all forms of art, though it

best reveals in beaten-metal artifacts, a technique which

village-blacksmiths used since ages for manufacturing hand-tools,

agricultural equipments, kitchen wares, things of day-today use.

Chhattisgarh has an abundance of iron ores. Traditionally, Chhattisgarh

tribes gathered rejected mass of iron, purified it by heating,

manufactured articles of daily use by beating it, and exchanged them

for food-grain etc. Simultaneously, from its surplus, they made

children's toys, forms of birds, animals, human icons, articles like

oil-lamps, tiny boxes, containers. Maybe, one day these artifacts

caught some art-lover's fancy and reached his drawing room and thus

this art began getting patrons. Bastar's paintings, bamboo-art,

wood-craft, brass-casts rendered using lost-wax technique, terracottas

all have a distinction of their own.

Bastar artist hardly abides by prescriptions - iconographic or

anatomical.

Even when portraying an upper class lady reading a book, he pursues his

own anatomical or iconographic whims. Caricatured extra large legs and

a coiffure, as large as her head, reveal his picture of the lady. Forms

are exceptionally simplified. An upright rectangle with four

exceptionally large strips defining legs and arms, and a form for head,

sometimes gilded metal-pieces used for identifying eyes and other body

parts, represent a human figure. Strips, comprising legs, are sometimes

turned on either side to become statuette's pedestal. Though isolated,

festive figures of musicians, their enthused faces glowing with

delight, force the viewing eye to see around them a celebration.

Indigenous Indian masses have behind them a long tradition of thought,

beliefs, conventions, customs, practices, diluted and instilled into

the routine of their lives. However, it is perhaps only a Bastar artist

who has a unique talent in giving to his form such thematic width that

in it reflects this entire past and the gist of its thought. Into a

form, something like a tribal rearing a bird, or transporting a dog,

sick, wounded, or tired, made from ordinary thrown-away pieces of tin,

the Bastar artist is able to entwine India's indigenous belief that

life is obliged to mutually sustain as without life there is no life.

Indeed, what distinguishes the Indian folk art from the entire body of

decorative art, from anywhere, is this thematic expansion - the

meaning, or the message that it reveals.

Folk Painting

Indian folk paintings are

divisible into three categories: professional, or commercial; votive

reproductions of deity-images; and, domestic. First two painting-types

are remunerative, while the third, aesthetic. Professional painting is

free to choose any theme, religious or secular; votive painting adheres

to the image-type it seeks to reproduce. Though now commercialized, a

domestic painting - a paper transform of traditional floor and wall

paintings, was initially ritual, decorative, and for personal delight.

Elaborate Madhubani compositions, indigenous paintings of Gonds of

Madhya Pradesh, Bengal folks, and pictographs of tribes like Warli of

Maharashtra, Saura of Orissa, Kurumbha of Tamilnadu, Santhals of

Bengal-Bihar, and Bhils of Gujarat-Madhya Pradesh define the domestic

idiom of folk art.

Professional Paintings

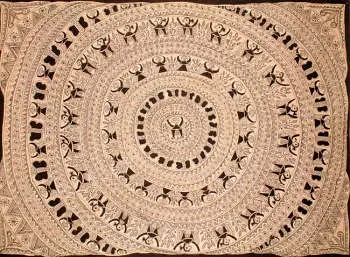

Tattoo Mandala |

Professional or commercial paintings comprise two types, the paintings narrating a tale that itinerant village performers - dancers-singers-actors, rendered for pictorially supplementing their performance, and the other, Godana or tattoos that tattoo-artists rendered for money.

A Rajasthani Phada Depicting Mahadurga |

The former is a narrative painting on a scroll-type large canvas, paper or cloth, unfolding horizontally or upright. Its themes are usually India's great classics, legends, or local folks.

Gangavatarana And Other Myths |

This comprises the earliest example of art for public away from court and temple. Local traditions apart, Paithan paintings of Maharashtra's chitrakathis, Rajasthani pars, and scrolls of patuas or jadu-patuas of Bihar and Bengal are some of its more significant examples.

Handwoven Black Paithani Sari With Zari Pallu |

Chitrakathis' paintings from Paithan, the ancient Pritishthan, a major township and business center those days, illustrate epical tales, especially the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, and sometimes narratives like Vetal-Panchavishi. Now Paithani is better known for its textile designs and a Paithani sari is a prestigious collection for any wardrobe.

Basag Phad |

Rajasthani counterparts of Maharashtra 's chitrakathis are known as

Bhopas. The Rajasthani pars - scrolls, narrate the epical legends of

Devanarayana and Pabuju, the examples of unique velour and

unprecedented sacrifice. Pabuju's legend being more prevalent, these

scrolls are often called as Pabuju-ki-pars.

Patuas, or pata - scroll

painters, of Bihar and Bengal illustrate both, episodes from great

epics as well as local folks. Some patuas confine themselves to magic

tales and are hence known as jadu-patuas, magic-scroll painters. In

West Bengal Midanapur region is a known seat of scroll painting.

Midanapur patuas not only narrate the tale when displaying the scroll

but also, when illustrating it on their canvas to capture its essential

spirit. The tradition of these itinerant singers still prevail and is a

significant source of entertaining a large part of village population.

Godana

Godana, or tattoos, till recent

past the art of backward rural masses, is also a commercial art by

which a tattoo-artist earns his livelihood. Till recent past, among

tribes and low-caste Hindus Godana, besides beautifying body, was an

essential requisite of a married woman for a marriage was sanctified

only after the bride had at least two sets of Godanas on her body, one

for her in-laws, and other, for her parents. Unless tattooed, her

in-laws did not accept even water from her hands. The Godana motifs

were religious, auspicious, and sometimes secular. Demand for new

motifs compelled tattoo-artists to conceive new forms and maintain an

album. Thus, paper transforms of tattoo motifs emerged and a new folk

art form was born. What an irony, tattoos that with their ethnic look

define today one of world's latest fashion trends and adorn body parts

of ramp-icons world-over, male or female, was despised, till a couple

of decades back, as a crude ugly thing of barbarians.

Reproductions Of Deity-Images : Orissa And Nathdwara

Sri Nath Ji |

Votive reproductions of Shrinathji at Nathdwara in Rajasthan,

The Trinity of Balarama Subhadra And Krishna at the Temple of Jagannatha |

or Jagannatha at Puri in Orissa, pursuing exact image-types, define yet another class of paintings. Initially rendered on cloth these paintings were identified as pata-chitras - cloth paintings. The term pata has many connotations, its most accepted meaning is however cloth. The Oriya tradition perceives in cloth a different kind of sanctity. Cloth is one of the main components used in making temple images of Jagannatha, Balarama and Subhadra. As is the practice, plain featureless neem-wood-images of Jagannatha and others, which are annually re-painted and periodically replaced, are first wrapped with several layers of cloth to arrive at a smooth surface and then painted. These cloth-layers better retain colors and their brilliance. Thus, the visible forms of deities enshrining Puri temple are actually those on cloth realized in colors. Hence, Jagannatha's reproductions on cloth are believed to have the same sanctity as the original temple image.

Worshipping Shri Nath Ji |

Jagannatha's image is votive while Shrinathji's, in act. This pre-determines their image-types in two art schools. Oriya reproductions of the Trio are simple votive portraits, while those of Shrinathji at Nathdwara represent his lila-rupa. Even when Shrinathji is reproduced with a large size central image, the Nathdwara pata portrays aspects of his lila around. Correspondingly, the canvas size of Nathdwara-patas is relatively larger.

Sri Jagannath Pati |

So vary their uses.

Orissa-patas are usually the images for domestic shrines but

Nathdwara's, usually the votive-aesthetic hangings. With this specific

use Nathdwara wall-hangings are called Pichhawais, not pata-chitras. In

Orissa pata-chitras, the focal point is its traditional style of

painting and its image-type, which is static from at least the 11th

century. Other subjects, secular and even romantic, also figure in

them, reproduction of temple images is however their main theme.

Meditating Chaitanya Mahaprabhu With Shri Krishna |

For other icons, human or

divine, these pata-chitras pursue Orissa's regional iconography - large

eyes, angular chin, pointed bird's beak type raised nose, and robust

look.

The form of temple images is akin to some folk tradition, which some

scholars relate to Sauras, an aboriginal tribe of Orissa. They contend

that Sauras worshipped wooden images of the Trio with identical

iconography till at least 11th century. In 11th century, they were

shifted to the newly built temple at Puri and installed as Jagannatha.

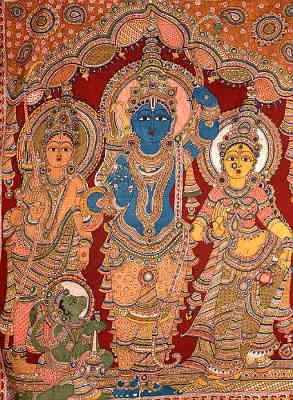

Kalamkari

Fluting Krishan With Gopis |

Kalamkari, a large-size cotton fabric patterned through the medium of dye, used as a hanging usually in a temple but also in private apartments on auspicious occasions or for decoration, is partly the Pichhwai type and partly pata-chitra, though in its style of rendering it is akin to the narrative cult of performers' scrolls.

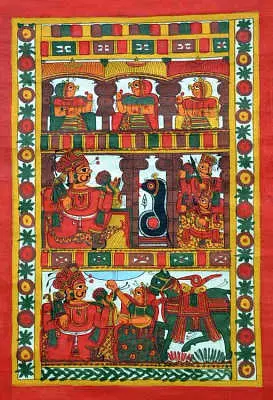

Shri Rama Durbar |

More expansive than a scroll,

sometimes with a length and width in meters, a single Kalamkari,

divided into many registers and spaces, covers an entire epic like the

Ramayana or the Mahabharata, its fifty-sixty episodes or even more.

Isolated deity-images, Vishnu's ten incarnations, are also painted but

its usual themes are rituals like tree-worship, legends like Devi

annihilating Mahisha or Shumbha and Nishumbha, episodes from

Krishna-lila - stealing Gopis' garments, killing a demon, besides the

great epics and other classics, and sometimes flora and fauna and

similar decorative motifs.

Kalamkari and Traditional Design Heritage of India |

Different from a Pata-chitra

which derives its name from its medium 'pata', and a Pichhwai, a name

characteristic of its use as a wall hanging, Kalamkari derives its name

from its technique, though now, not so much for its technique, a

Kalamkari is known for the type of motifs and iconographic forms which

have almost concretized. The term Kalamkari literally means the work of

'kalam' - pen or feather, though besides, a Kalamkari is also

block-printed. Earlier only the outlines were block-printed but for

finer details colors were applied freehand with a brush or feather.

Obviously, it was for this finer part of its work that the artifact was

called Kalamkari. Now this distinction has largely blurred. As in case

of brush and block, distinction in types of colors has also blurred.

Ahmedabad in Gujarat, and Kalahasti and Masulipatan in Andhra are the

known centers of Kalamkari.

Gujarat has two other classes of painted cotton, 'chhit' - spotted

cotton, and 'chintz' - fabric with pictures. Being one among others,

Kalamkari did not have in Gujarat such distinction as in Andhra with

the result that Kalamkari is more widely known as the art of Andhra

rather than Gujarat.

Domestic Painting

Domestic painting has its roots

in rock-shelter pictographs. Harappan drawings on its pottery, as well

as animal and human forms in its terracotta figurines, reveal

continuity of these pre-historic pictographs. Human and animal figures

on early coins adhere to same iconographic forms. Tattooing, perhaps an

art prevalent across ages, has similar line-drawing technique as had

rock-shelters. Floor drawings and wall paintings, a part of

marriage-like auspicious rituals, represent the final stage in the

growth of folk-art from rock-shelter drawings to canvas painting. It is

essentially this common tradition that imparts to art-styles of most

tribes - Bhils, Warlis, Gonds, Kurumbhas, Sauras, Santhals and others,

striking similarity.

A folk painting is composed of overlapping forms, irrational anatomy, irregular imagery, and random motifs but its polyphonic character has an amazing coherence and unity; perhaps, because its images are endowed with the power to speak to each viewer in his diction and tell him his tale. This apart, born of the tradition under which it was part of a ritual, or deity-feast, marriage, birth, festival type sacred or auspicious occasions, a folk painting is endowed with underlying spiritual tones, which thread into an unseen unity its apparent diversities. This spiritual connotation is folk painting's essence, spirit and soul. To the artist, individual in his act is heroic, but along it myriad other events keep unfolding, and the artist finds his world widening beyond this individual and beyond his act. To the folk artist the world is not an individual's island. So to him is time, a continuum and indivisible process. Hence, in his art, events of past, future and present exist in simultaneity, and legends, myths and fantasy - things of far gone days, are found interwoven with the contemporary. In his epic one story unfolds into another and so on in an endless chain.

Ritual Painting of Goddess Lakshmi for Worship |

In folk art, ritualism rarely reflects but it has always sustained in ritualism.

Folks believed that gods

blessed with their presence a house only when it consecrated for them

sacred spaces. This gave birth to the cult of floor drawings and wall

painting which separated from profane the gods' sacred spaces and

realized their divine presence in motifs drawn along. Floor-drawings,

variedly known as Rangoli, Alpana, Ossam, Jhunti, Kolam, Mandana,

comprised sacred symbols, mystic diagrams, auspicious motifs, flora and

fauna, geometric patterns. In addition, wall paintings, figural by

nature, comprised divine icons, legends. Paintings' such contents

apart, its entire tradition had ritual connotation. The skill of

painting was believed to be a divine gift made to a woman, essentially

a married one, a Suhagin. As both, marriage and painting, represented

fertility, a Suhagin alone could accomplish a painting. In all ages,

one Suhagin, or another, was found claiming appearance of a female

divinity, usually Parvati, in her dream and gifting to her the skill to

paint and giving her an understanding of reeti - convention, and

knowledge of cosmic laws. Commercialized, the painting of tribes might

have lost its ritual status but not its ritual connotations, its

intrinsic quality and ability to transcend the flesh and reach the soul.

Domestic Folk Painting: Tribal And Non-Tribal

Marriage Procession of the Warlis |

Tribal and non-tribal -

Madhubani, Bengal, are two distinct painting-types. Tribes' art

breathes closer affinity with rock-shelter art. Geographical boundaries

are irrelevant in both but in tribal art almost absolutely. In Warli

painting, a village is seen running into a town, and town, into a big

city, and so on. A two-color composition as is Warli, or multi-colored,

a painting of tribes has a set of more simplified imagery and

composition.

The Tragedy of 9-11 |

Bengal folks, or even Madhubani, adhere to norms of anatomy and

iconography, and even to hierarchical or social order. Not these alone,

tribal paintings do not abide even by figures' relative sizes. They

conceive a scorpion or caterpillar with the same size as a cock or

horse, and see no anomaly in it, as if some internal logic regulates

them. Folk paintings, especially Warli, use spatial divisions of canvas

for portraying simultaneous operation of a number of activities of the

same genre - ripening of crop, harvesting, transportation, stacking of

bundles, thrashing, separating corn, revealing a kind of rhythmic

synchronicity, something not seen in non-tribal folks. They have as

different attitudes in portraying violence - terror, hunting, animal or

human sacrifice. Madhubani compositions have abundant motifs relating

to violence. Contemporary terror theme apart, the Bengal folks portray

acts of male cruelty against a woman and even human sacrifice. Scant

fishing activity or a hunt-transporting icon apart, in tribal paintings

violence rarely figures. Whatever in their real life, the tribes do not

pollute their art with scenes of killing or cruelty for to them a

painting is the seat that gods enshrine.

Flora and Fauna |

In non-tribal paintings nature

is a rarity, and landscape, rarer. Tribal painting is more sensitive

about nature. To their randomly jotted figures or activities, landscape

affords compositional unity. In entire tribal art man and nature are

alike essential component of existence. In field or forest, grazing

cattle, harvesting, or transporting firewood, or fodder, it does not

distinguish man from his surroundings. Apart, in its treatment of

nature it is exceptionally sensitive. Paintings of Gond tribe treat

animals with same sensitiveness as one treats a child, conceiving them

as multi-colored, grafting on a tiger's face a child's innocence,

curiosity and enthusiasm for life, or allowing a mouse to overlap into

the form of Ganesh, its patron. The use of bright basic colors without

shading is characteristic of the entire body of folk painting but in

tribal art, Gond in particular, colors are more vibrating and create

movement and rhythm.

Lost in the Forest |

When shifted to paper Warli

artists retained their initial scheme of geru - red mud, for

background, and white for forms.

Kurumbhas render both, a two-color as well as multi-color composition.

Bhils distribute the canvas space into small circles, triangles,

minuscule towers or temple motifs and use in them deep bright colors in

striking contrast.

In tribal paintings, forms are extremely simplified. In Warli paintings

a configuration of fleeting lines defines a bird, and a series of

revolving circles, the sun. In other paintings, as Bhils', the sun is

conceived as a spiked circle with human face. Two length-wise elongated

triangles of the same size, one, upright, and other, inverted, a circle

for head, and two lines, for arms, and other two, for legs, define a

human figure. In Kurumbha paintings an upright rectangle substitutes

this two-triangle-formation of human figure. In paintings from Sarguja

and Bastar, in Chhattisgarh, upper triangle has a size larger than the

other. Sauras conceive human figure with just one elongated triangle.

The style of costumes and modeling of figures in Bhils' paintings are

somewhat urbanized. As simply are identified genders. A single circle

for head denotes a male, while an additional one, denotative of

hair-dress, annexed to the former, denotes a female. As simple are

animal forms. Two horizontally drawn triangles, as those of human

figures, constitute an animal figure. A rectangle, straight or curbing,

sometimes substitutes this two-triangle-formation. A few vertical lines

under the hind legs, denotative of thuds, denote a cow or female

animal. Hardly optical, these distinctions emerge from interpretation,

a tribal painting's basic feature. In any case, the tribal art paints a

thing's essence, not the thing.

Madhubani And Bengal Folks

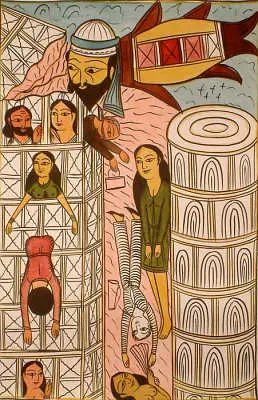

The Terror of Osama bin Laden |

The non-tribal Madhubani and

Bengal paintings are theme-oriented and form-consistent. Even randomly

jotted, motifs and forms reveal a conscious effort in their

composition. However large the number of motifs, a Madhubani painting

has at least a central theme. Bengal 's Kalighat folks had begun

transforming into bazaar art by around 1890-1900. Hence, it inclined

towards sophistication and visual accuracy. It developed accomplished

imagery as suited the market. Kalighat painting initially reproduced

Kali-images but subsequently their number or even those representing

religious myths, legends, reduced to almost nil. Instead, rigid social

customs, festivals, celebrations, pictures of Europeanized life-style

were more favored. The period from late 19th century onwards was a

great era of art in Bengal. Institutions of art like Shanti Niketana

apart, Bengal had a galaxy of eminent painters in modern art-styles.

Their influence transformed Bengal folk into a semi-civil art. Now its

themes are terrorism, demonisation of terror symbol like Osama bin

Laden, warning against AIDS.

Madhubani, the painting style practised around Mithila in Bihar with

village Madhubani as its center since ages, emerged into global focus

around 1970 and is now world-wide most demanded art-form of India. In

1970s itself it impressed art world by the magic of its pure colors,

rich and elaborate composition and ability to lead the viewers to an

India - the truest, to which they have no otherwise access. Now hardly

in an average man's mind, Mithila had, instilled into its people's

blood, a set of myths, legends, beliefs, traditions, customs, rituals,

festivals, practices, and these are what flow from the Madhubani

painter's brush as its vision of India, the India that wakes gods after

four monsoon-months by performing rites around sugarcane plants and a

couple of footprints - Lord Vishnu's, walking on a chain of lotuses

leading to an empty sanctum sanctorum, the India where a maiden, before

entering into marriage-ties, worships the earth seeking from the Mother

goddess blessings of fertility, the protective Pipal tree, for giving

her a roof, or where a deadly cobra is seen dancing to the notes of

snake-charmer's pipe. Whatever, a myth, legend, event or occasion, a

Madhubani painting represents in a series, various steps, episodes, or

a repetitive chain.

It is in the cult of floor-drawing and wall painting that the roots of

Madhubani painting lie. In its broad layout it pursues floor-design -

Alpana format. The central theme apart, like an Alpana a Madhubani

painting adorns its entire field with motifs and images, even

incoherent or random. It inherits its divine imagery, myths, legends,

narratives and all its dialogues - its unique feature, from

wall-paintings. In Madhubani paintings images often eject and begin

discoursing. Conceptualization apart, the Madhubani painting also

reproduces now highly stylized forms, even abstract, experiments with

them, deity-forms in particular, resorts to deliberate symbolism and

inclines to be more decorative. Terrorism like concurrent themes often

frequent its canvas. Short heights, expressive and angular faces in

profile, large bulbous eyes, sharp noses, and typically styled hair

define Madhubani's male and female figures. However insignificant,

almost every image has its role. Massive symbolism, underlying rhythm,

great width of imagination, strong lines, versatile and vibrant

imagery, vigorous composition, elaborate borders are other features of

Madhubani art idiom.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Gurusaday Dutt : Folk Arts and Crafts of Bengal

- Das Gupta : Alpana

- R. N. Ganguli : Pata and Patuas of Bengal , in Indian Folklore

- Heinz Mode/ Subodh Chandra : Indian Folk Art

- Upendra Thakur : Madhubani Painting

- Michel Postel/ Zarine Cooper : Bastar Folk Art

- Elwin : The Tribal Art of Middle India

- S. Fuchs : The Gond and Bhumia of Eastern Mandala

- The Cult of

Jagannath and the Regional Tradition of Orissa : ed. A. Eschmann, H.

Kulke and G. C. Tripathi

- Five

Contemporary Folk and Tribal Artists of India : ed. Jyotindra Jain

- Marg Volume :

Homage to Kalakari (April, 1979)